a prefatory note.

Welcome, or else welcome back! As many of you already know, I am a relative beginner to Inform 7. Some of you might be, too. That’s great! We can be beginners together. My primary purpose in writing this blog is to make introductory content. It can be intimidating to start out with Inform, so I thought I’d carve out a space for newcomers like us to learn more about it. I love Inform 7; I think it’s great fun. There may be better ways to do anything that I do here, but sometimes making something that works is more than enough. My message is this: Inform is for everyone.

Let’s make IF!

other options.

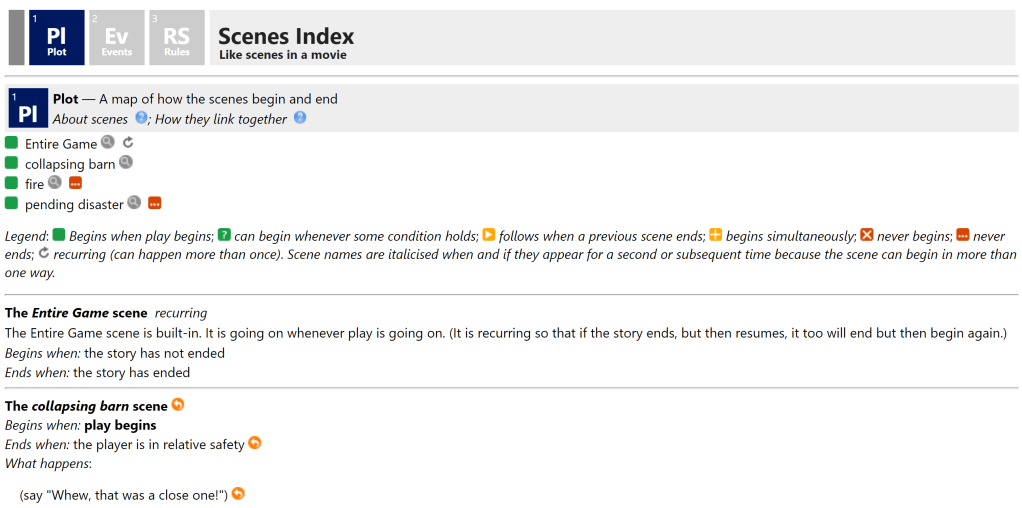

If you’ve been reading this series for a while, you might be wondering: what about scenes? Scenes are used extensively in my other project, Marbles, D, and the Sinister Spotlight, and I’ve written about that here. What are they? Scenes are a way to sculp a sort of temporal geography in a game. They begin and end based on certain conditions, and, while they are happening, we can customize action processing or printed output.

fire is a scene. fire begins when play begins.

the burning house is south of relative safety.

instead of going south from relative safety when the fire is happening:

say "No way. I'm not going into a burning house."And yes! Inform keeps count of passed turns (though it insists upon calling them minutes) within scenes, making it easy to have a countdown (or “count up,” in this case).

the ramshackle barn is a room. it is in the disaster area.

collapsing barn is a scene.

collapsing barn begins when play begins.

collapsing barn ends when the player is in relative safety for the first time.

when collapsing barn ends:

say "Whew, that was a close one!".

before doing something when collapsing barn is happening:

if time since collapsing barn began is three minutes:

end the story saying "uh-oh.".

every turn when collapsing barn is happening:

let the escalating danger be time since collapsing barn began;

say "[if escalating danger is zero minutes]The floor wobbles beneath you.[otherwise if escalating danger is one minute]The ceiling shakes above you.[otherwise if escalating danger is two minutes]You are running out of time. The barn is about to fall on your head![otherwise]This condition should never occur. What an embarrassing turn of events!".I think it’s clear that there is a higher up-front cost for this approach. Assigning a number to a group of rooms can be done in two lines of code. Using phrases like “countdown of the location” allows us to write general code that works in specific ways that are relative to the state of the game world. It’s efficient, and the examples from last time are pretty easy to understand. Why would we ever use scenes for this type of thing?

Scenes don’t, out of the box, do things that we couldn’t do with a bunch of custom variables and rules. This is stated explicitly in the Inform 7 documentation. However, because they are a core feature Inform 7, we have a lot that’s already built for us. They also are well suited to what is arguably Inform 7’s greatest strength, readable code. “Every turn when collapsing barn is happening” is not just easy to read; it’s easy to imagine. Still, we could just as easily change our “countdown” to some other named value if it helped us make sense of a simple number that varies.

It is great giving a value to every room, but we’ll need to do some more work–things we didn’t consider last time–to contain things. If only four rooms in the game need a countdown, we’ll need to think about the implications of assigning one to every room. Do we create a region, put the four rooms inside of it, then name the region in our every turn rules? The scene approach requires more setup but our code is far less likely to escape its confines. Giving a value to everything and checking it every turn is “big” code.

Obviously, we always want Goldilocks code. We want it to be perfectly sized, but sometimes one has to pick their poison.

The greatest selling point of the scenes strategy is this: scenes are organized–with links–in the project index. This is very powerful and is a great help in a large project. It’s hard–and my own experience with Repeat the Ending can attest to this–to keep track of a bunch of loose values. RTE is 152k words! If only I had understood scenes at the time.

While there will always be occasions where a simple number value makes more sense, I am growing more and more enamored with scenes lately. I like that I don’t have to remember a lot of number values or global states. It’s harder to get started with them, but it is worth it end the end. I’ve written quite a lot about them, but I feel like I’ve only scratched the surface.

In my current project, the “cave game,” there is a whole lot of collapsing and counting and exploding going on. I’d like the opening to be very exciting, with tension but without frustration. I’m not sure if I can pull that off! There are several rooms–more than those used in our sample code. Let’s get a count of those rooms, which are all in a region called “greater earthquake territory.”

gting is an action applying to nothing.

understand "gt" as gting.

carry out gting:

let room count be 0;

repeat with place running through rooms:

if place is in greater earthquake territory:

say place;

say line break;

increment room count;

say "total rooms: [room count]";

say "[line break]".This should get us names and count of every room in my “greater earthquake territory” region via a *GT* command. Here’s the output:

>gt

Button Room

Engravings Room

Damp Passage

Junction

Endless Stair

Creepy Crawl

Royal Hall

Great Door

total rooms: 8So, with the current options under discussion, we’d have either eight countdown values or else eight scenes. Or… would we? Let’s jot down some requirements:

- eight sequentially connected rooms.

- this is a one-way trip; once the player moves, they cannot go back.

- after the player has been in one of these rooms a certain number of turns (3?), something happens (death? probably nothing so serious, but something).

- dramatic, environmental text should print every turn (less/more?) to keep pressure on and make the danger visible.

- there may be a couple of “solace” rooms in the middle that do not collapse, but there should still be some flavor text printing after turn processing.

That’s a lot to do! Now, I do need to take care not to share too much, as this is a competition piece, but I think I can at least share some coding ideas next time. I’ll share a concept for tracking turns in a series of rooms, with some kind of non-death event when a specified amount of time elapses.

etc.

What else is going on? This may be the last post here for the week, as I would like to make some progress on Trinity. Some of you–quite reasonably–have wondered what is happening there. That would include a Gold Machine post, as well as a podcast about both versions of Graham Nelson’s “The Craft of the Adventure.” Here’s hoping! I have a post about Victor Gijsbers’s The Game Formerly Known as Hidden Nazi Mode in the oven, too.

I’ve also been streaming non-IF titles on twitch and porting them over to YouTube. I’ve completed a full walkthrough of From Software’s Elden Ring and have begun streaming Arkane Austin’s (RIP) Prey. The Elden Ring series is also up at YouTube.

I’ll probably do a formal project announcement for the “cave game,” title and all, in the near future.

next.

this place is coming apart!

Leave a comment